What a Powerlifter Taught Me About 'The Art of War'

When Physical Culture Intersects with the Metaphysical

I recently read Sun Tzu’s The Art of War for the first time. Going into the reading, I expected my Western viewpoint and what little I knew of Chinese metaphysics to influence the way I interpreted the material. What I did not expect to shape my understanding of this over two-thousand-year-old work was, of all things, something I’d heard on a powerlifting podcast.

‘About the sixth or eighth time that I read The Art of War, I realised that it wasn’t about being a warrior at all. It wasn’t about war. It was about avoiding war.’

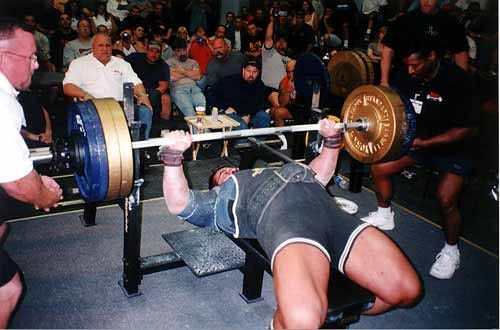

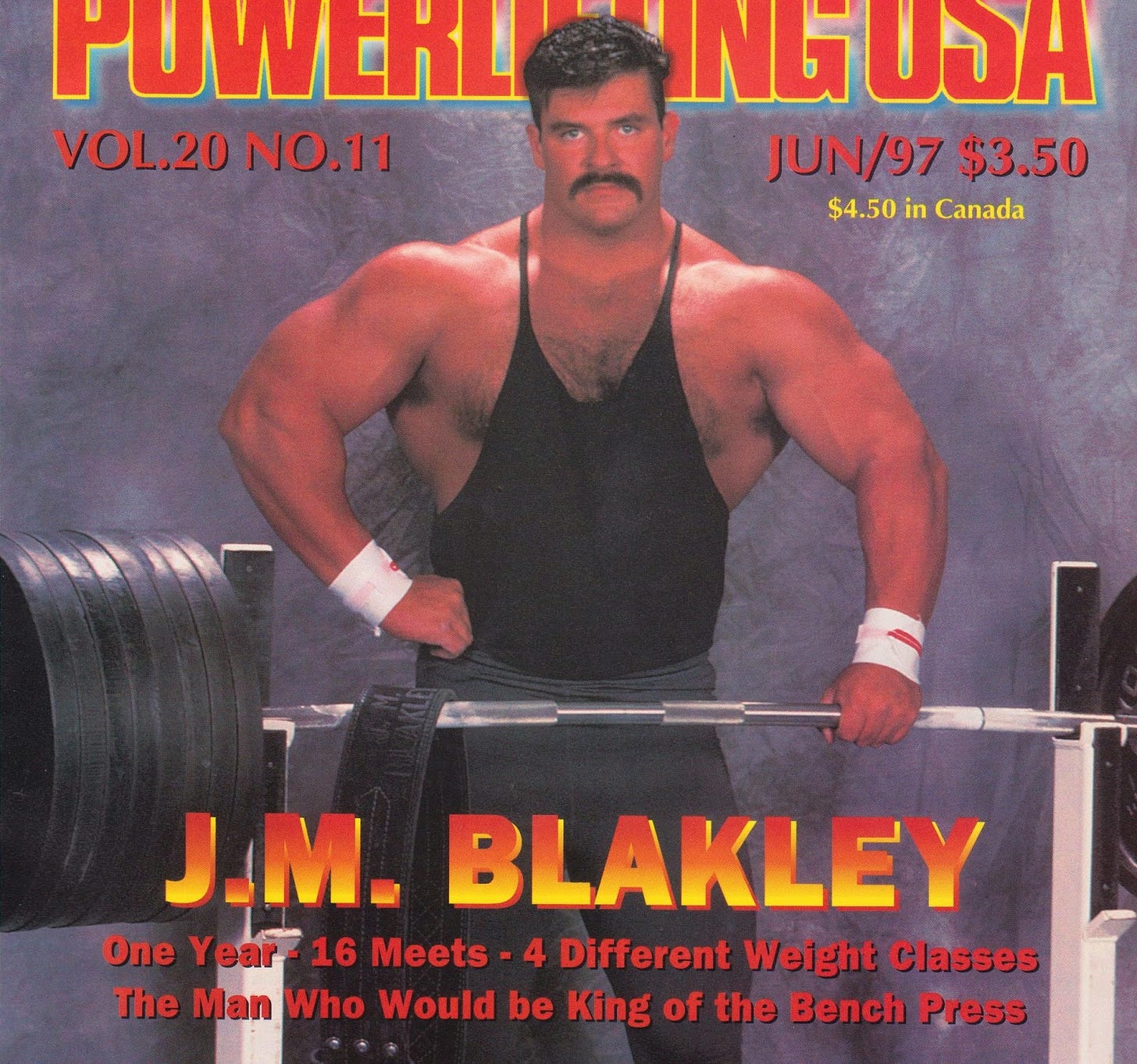

These are the words of JM Blakley, a strength coach, columnist, and multi-time world record winning powerlifter (Schulte, 2019; elitefts, 2023, 3:05:23). He’s known for giving his name to the JM press, a powerlifting assistance exercise that anyone who has spent fifteen minutes on the strength training side of the internet will be aware of (although, sadly, it remains underutilised by the general gym-going population). He’s also part of an underground subculture of educated, dialectic strength fanatics who spend at least as much time thinking about and talking about training and coaching as they do partaking in those activities.

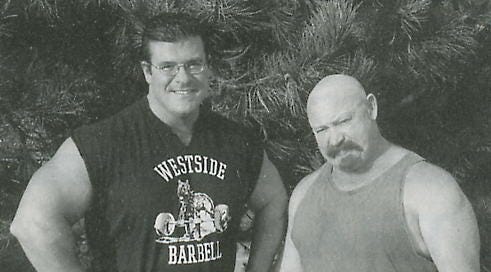

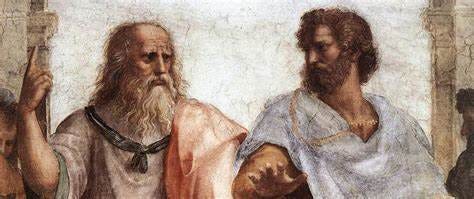

One might describe them as “cultured meatheads” (if one dared to). Not quite philosopher kings, no, but that’s mostly because, presumably to the dismay of Plato, philosophers and kings are not yet one and the same, and JM Blakley, who may very well spend the bulk of his time on philosophy, is not being periodically called up by the state to take part in the weary business of politics. Some of the members of this community are certainly old enough to be Rulers in Plato’s ideal state; to the best of my knowledge JM Blakley and Dave Tate (pictured below) are in their fifties, over the age requirement of fifty years set out in the Republic (Plato, 2003). Individuals such as these two differ from the more mainstream archetype of the vapid, simpleminded lifter. Appearing deeply affected by philosophic and scientific studies, they are reminiscent of the Imperial Chinese conception of a “cooked” barbarian, while their knucklehead counterparts can only be of the “raw”, uncultured kind.1

Blakley, and others like him, provide a reassuring and seemingly incredibly rare example of someone achieving great success in one walk of life pivoting to another without becoming embroiled in blatant pseudo-intellectualism. Usually, when a podcast gets off track, with guest and host beginning to discuss a rogue topic, I do not find myself rejoicing; many of us can surely relate to the experience of listening to podcasts ostensibly about wildlife, sport, science, etc. that end up spending the bulk of their time on topics such as cancel culture and conspiracy theories. The advice that I often find myself telling my friends – “If you want history, go to a historian; if you want science, go to a scientist; if you want theology, go to a theologian; etc” – seems in need of reconciliation with my joy at listening to JM Blakley discuss morality or worldview or Taoism. After all, here I am getting my philosophy from a powerlifter.

So, what exactly is Blakley’s interpretation of The Art of War? Is it consistent with the source material, and to what degree does it differ from previous understandings of the work? Blakley (in elitefts, 2023: 3:05:40) describes his realisation, after half a dozen or more reads, as such:

‘It [The Art of War] was all about not going to war. It was all about winning without firing a shot, being so overwhelmingly powerful, making yourself so overwhelmingly powerful, that when you show up, the enemy surrenders. And that way, you lose nobody, they lose nobody, you absorb them into your group. You don’t destroy them or destroy their land; they become part of you. You win without the battle, without the destruction. And that has to happen before you go to war.’

Blakley’s interpretation of The Art of War can perhaps be summarised in two key points: first, the goal is to avoid battle, which can be achieved through a pre-emptive arms buildup sufficient to intimidate the enemy into surrendering; second, integrating the enemy into your own community, thus increasing your own strength, is preferable to destroying them.

Those of you acquainted with The Art of War might find the first point entirely unsurprising. In an oft-cited verse from the third chapter of the classic, Sun Tzu, in the Thomas Clearly translation, lays it out as such:

‘Therefore those who win every battle are not really skillful – those who render others’ armies helpless without fighting are the best of all’ (Sun Tzu, 1991:18).

This verse is translated in a multitude of ways, but all translations preserve the same essential philosophy and dichotomy. In the Lionel Giles translation, it is phrased as ‘Hence to fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence; supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting’ (Sun Tzu, 2012:5). And in the Samuel B. Griffiths translation (perhaps my favourite version of the quote), ‘To win one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the acme of skill. To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.’ (Sun Tzu, cited in Corneli, 1987:419).

Blakley’s second point is also evident in the source material. In Chapter 2, Sun Tzu prescribes treating captured enemy soldiers in this way (from the Clearly translation):

‘Change their colours, use them mixed in with your own. Treat the soldiers well, take care of them.’ (Sun Tzu, 1991:15).

This verse stresses the integration of the enemy, who should not be mistreated simply because they were formerly opposed to you. (Giles translates this part similarly, albeit with more detail, as ‘Our own flags should be substituted for those of the enemy, and the chariots mingled and used in conjunction with ours. The captured soldiers should be treated kindly and kept.’ [Sun Tzu, 2012:4]) Advocating for more than the simple subjugation and enslavement of the enemy, this verse lends credence to Hwang and Ling’s (2005:1; 2008:Abstract) assertion that Sun Tzu’s writing was shaped by a ‘cosmopolitan’ worldview and ‘cosmo-moral’ world order, in contrast to the imperial hypermasculinity that they identify in the action of the Bush Administration and reaction of others, including China.

More than the quotes we have seen thus far, there is a single verse that encapsulates both key points of Blakley’s interpretation. In the Clearly translation, following on from the verse beginning ‘Change their colours…’ (see above), Sun Tzu (1991:16) summarises his approach, both to battle and the integration of the enemy:

‘This is called overcoming the opponent and increasing your strength to boot’.

The Giles translation similarly phrases it, as such:

‘This is called, using the conquered foe to augment one’s strength.’ (Sun Tzu, 2012:4)

And, therefore, it seems safe to say that the conclusions the powerlifter draws from The Art of War are logical and appear perfectly legitimate. Perhaps, more than a person ready and willing to taste every branch of learning, JM Blakley is a philosopher in the truest sense. He certainly seems awake when it comes to his analysis of Sun Tzu – or, at the very least, he is dreaming a realistic dream.

Mindsets East and West

‘Let’s see how tolerant your Western mindset is and if it can tolerate maybe a little bit of Eastern ideas.’

This is how JM Blakley begins a 2020 YouTube video titled ‘THE TAO OF TRYING’ (JM7thlevel, 2020). In the video, Blakley attempts to articulate the difference between being passive and flowing, a point that, to the layman, seems to balance somewhere between nuance and nonsense. There is perhaps no quote that better encapsulates Blakley’s overall philosophy than this. The existence – and juxtaposition – of Eastern and Western mindsets is at the core of his thinking, along with the idea that they can complement each other; ‘a little bit of Eastern ideas’ goes a long way in adapting to certain situations.

When Blakley interrogates the Western mindset, testing its openness to new, exotic-seeming ideas, this is not to disregard Western thinking or to belittle its importance. Condensing the Western mindset to one of hustle and effort, the Eastern to one of flow, he advocates a mixed approach, to powerlifting and to life; ‘a little bit’ of this, ‘a little bit’ of that. Far from rebellious or contrarian, Blakley avoids dogma for the kind of strategy that, though one might unfavourably describe it as fence-sitting, has a nuance that is likely to be attractive to many in the twenty-first century. Although it may be amateurish to liken this philosophy to the concept of yin and yang, at the core is an idea that Eastern and Western ideas both oppose and complement one another.

Comparing and contrasting philosophies from the East and West is nothing new. McNeilly (2011) contrasts Western and Eastern views in the realm of business, identifying stockholders as the main motivation for Western businesses, while Asian businesses are said to exist (in an arguably more communal, holistic manner) primarily to provide jobs for their employees. (McNeilly’s book is the kind that your business professor would love, a captivating combination of case studies and name-drops with an ostensibly innovative, dubiously appropriated philosophy.) Micciche (2021), applying The Art of War in a purely martial context, contrasts Napoleonic Era theorists (your Clausewitz, your Jomini, your Bonaparte), who could feasibly be considered “Western”, with Sun Tzu, who is undeniably and prominently “Eastern”. Attempting to combine ideas Eastern and Western is not unique to Blakley either; as Blakley complements Eastern and Western philosophy in life and lifting, Micciche (2021) contends that theories in The Art of War could help U.S. military personnel and policymakers develop alternatives to armed conflict, the context in which foundational Western theories are most appropriate, since, in a world shaped by nuclear deterrence and economic interdependence, conflict above the threshold of war is the least likely manifestation of competition. With the Western concept of the decisive battle taking a backseat, Sun Tzu’s recommendations on espionage, diplomacy and optics seem an increasingly useful complement.

Sun Tzu in the 21st century

Today, the influence of The Art of War has exceeded the military discipline, influencing diplomacy and politics, business and management, as likely to be quoted in a book on entrepreneurship as one on wartime strategy (McDonald, 2023; Zhou, 2015). Hwang and Ling, in a 2005 working paper, felt that The Art of War seemed more popular than ever (Hwang and Ling, 2005). In an updated version published in 2008, Sun Tzu still seemed more popular than ever; we can assume that the authors did not feel any decline in Sun Tzu’s popularity in the three intervening years.

How we apply lessons from The Art of War very much depends on our personal interpretations and contexts. For the aspiring entrepreneur or business executive, you might seek to subdue the enemy without fighting through, as Despin (2018) suggests, looking for untapped markets to penetrate instead of fighting over scraps in oversaturated markets. For the military strategists (and gamers who fancy themselves the next Alexander the Great because of their thousands of hours of playtime on Civilization VI), focus on when and, most importantly, when not to fight, master military manoeuvres, and learn the ins-and-outs of the six kinds of terrain and the nine grounds. For the world leaders struggling to navigate the tense geopolitical situation (I know there are a few of you reading this), Sun Tzu’s classic contains wisdom for operating below the threshold of open war, competing in deterrence and intimidation, and for information dominance.

And for the powerlifters, JM Blakley suggests this:

‘Don’t attack unless you know you can win. Retreat. Get stronger. Then attack and win quickly, with less waste.’ (elitefts, 2023, 3:07:45)

Effort and recovery are balanced on a knife edge. Knowing when to push intensity and volume, and when to back off to facilitate recovery is truly the acme of skill.

I would like to close out this article with a quote from JM Blakley. The rationale for including this here is to provide an uninterrupted glimpse of his analysis, to let the words speak for themselves. In the quote, Blakley talks about The Tao of Pooh, a book by Benjamin Hoff. In this short excerpt of his speech, the themes of Taoism and East-West balance which he so often talks about are evident. For more JM Blakley, see his many appearances on Table Talk, including episode 213, in which he discusses The Art of War, or episode 63, in which he gives book recommendations, including the Tao of Pooh (elitefts, 2021b, 1:19:30; elitefts, 2023).

‘I always talk about the Tao of Pooh, the T-A-O of pooh, ‘Tao’ meaning way, and it’s not a children’s book but the guy – it’s Benjamin Hoff, I think – he introduces you to a few ideas about Taoism and he does it in a very easy to read way. He’s having a conversation with Winnie the Pooh but he’s using Winnie the Pooh as this character who goes with the flow, who adapts and flows and doesn’t fight the world – and we don’t always have to fight. Our Western mind says that if you want something, you’ve got to put your canoe in the river and you gotta face it upstream and you gotta paddle like crazy because all the good stuff is upstream – and if it comes easy to you, it’s not good. But is that true, is all the good things up the stream? I don’t think so, right? So, some people have learned that sometimes you gotta – well, I can say I have learned – that sometimes you’ve gotta paddle like crazy upstream if that’s where you want to go but sometimes you can put your canoe in the water and you can let it take you somewhere wonderful, downstream.’

Out of the mouths of meatheads.

References

benchpresschampion (no date) James M. Blakley. Available at: https://www.benchpresschampion.com/CHAMPIONS/JamesMBlakley.htm (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

Corneli, A. (1987) ‘Sun Tzu and the Indirect Strategy’, Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali, 54(3), pp. 419-445. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42738671

Despin, T. (2018) ‘The Best Way to Win Your Way?’, Medium, 1 October. Available at: https://medium.com/swlh/the-best-way-to-win-your-war-c3153f3d7e3f (Accessed: 4 October 2024).

elitefts (2021a) Build MASSIVE Shoulders with JM Blakley’s Special Technique. 25 January. Available at:

elitefts (2021b) Dave Tate’s Table Talk with JM Blakley. 18 June. Available at:

elitefts (2023) J.M. Blakley | 710 LBS BENCHPRESS, JM PRESS, Meta-Physical, Table Talk #213. 3 August. Available at:

Fiskesjö, M. (1999) ‘On the ‘Raw’ and the ‘Cooked’ Barbarians of Imperial China’, Inner Asia, 1(2), pp. 139-168. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23615574

Gant (2009) If you wanna be the man, you gotta out-eat the man. Available at: https://70sbig.com/blog/tag/jm-blakely/#:~:text=This%20nugget%20comes%20from%20JM%20Blakely,%20a (Accessed: 5 October 2024).

Hwang, C.-C. and Ling, L.H.M. (2005) The Kitsch of War: Misappropriations of Sun Tzu for an American Imperial Hypermasculinity. International Affairs Working Paper 2005-02. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228371048_THE_KITSCH_OF_WAR_Misappropriations_of_Sun_Tzu_for_an_American_Imperial_Hypermasculinity

Hwang, C.-C. and Ling, L.H.M. (2008) The Kitsch of War: Misappropriations of Sun Tzu for an American Imperial Hypermasculinity. International Affairs Working Paper 2008-04. Available at: https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/wps/gpia/0016527/f_0016527_14283.pdf

J.M. Blakley Interview (1997) – Mike Lambert (2014). Available at: https://ditillo2.blogspot.com/2014/05/jm-blakley-interview-1997-mike-lambert.html#:~:text=J.M.%20Blakley%20(JM):%20I%20enjoy%20the%20challenge (Accessed: 5 October 2024).

JM7thlevel (2020) TAO OF TRYING. 3 July. Available at:

McDonald, S.D. (2023) Sunzi, ‘shì’ and strategy: How to read ‘Art of War’ the way its author intended. Available at: https://theconversation.com/sunzi-shi-and-strategy-how-to-read-art-of-war-the-way-its-author-intended-200807#:~:text=Sunzi%20is%20concerned%20about%20long%20supply%20lines,%20because%20they%20lower (Accessed: 3 October 2024).

McNeilly, M.R. (2011) Sun Tzu and the Art of Business: Six Strategic Principles for Managers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Micciche, J.P. (2021) The Art of Non-war: Sun Tzu and Great Power Competition. Available at: https://warroom.armywarcollege.edu/articles/non-war/ (Accessed: 1 October 2024).

Plato (2003) The Republic (Translated from the Greek with an introduction by D. Lee. Further reading compiled by R. Kamtekar.) 2nd edn. London: Penguin Books.

Most, G.W. (1996) ‘“The School of Athens” and Its Pre-Text’, Critical Inquiry, 23(1), pp. 145-182. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1344080

Schulte, S. (2019) Introducing New elitefts Columnist and Coach JM Blakley. Available at: https://www.elitefts.com/news/introducing-new-elitefts-columnist-and-coach-jm-blakley/#:~:text=JM%20Blakley%20is%20known%20for%20being%20the%20namesake%20of%20the (Accessed: 3 October 2024).

Sun Tzu (1991) The Art of War (Translated with preface and introduction by T. Clearly.) Shambhala Pocket Classics edn. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Sun Tzu (2012) Sun Tzu on the Art of War: The Oldest Military Treatise in the World (Translated from the Chinese by L. Giles.) Available at: https://globalintelhub.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/The-Art-of-War-by-Sun-Zu.pdf (Accessed: 11 October 2024).

Further Reading

The Lionel Giles translation of The Art of War is available in its entirety for free online from Project Gutenberg.

The basic text:

Sun Tzu (2012) Sun Tzu on the Art of War: The Oldest Military Treatise in the World (Translated from the Chinese by L. Giles.) Available at: https://globalintelhub.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/The-Art-of-War-by-Sun-Zu.pdf (Accessed: 11 October 2024).

With an introduction and critical notes:

Sun Tzu (2012) Sun Tzu on the Art of War: The Oldest Military Treatise in the World (Translated from the Chinese with Introduction and Critical Notes by L. Giles.) Available at: https://ebook-mecca.com/online/TheArtOfWar.PDF (Accessed: 11 October 2024).

For an overview of Raphael’s fresco, seen above:

‘The School of Athens’ (2024) Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_School_of_Athens#Figures (Accessed: 5 October 2024).

For an examination of the ‘raw’ and ‘cooked’ classification, see Fiskesjö (1999).